A good cook changes his knife once a year—because he cuts. A mediocre cook changes his knife once a month—because he hacks. I’ve had this knife of mine for nineteen years and I’ve cut up thousands of oxen with it, and yet the blade is as good as though it had just come from the grindstone. There are spaces between the joints, and the blade of the knife has really no thickness. If you insert what has no thickness into such spaces, then there’s plenty of room—more than enough for the blade to play about it. That’s why after nineteen years the blade of my knife is still as good as when it first came from the grindstone.

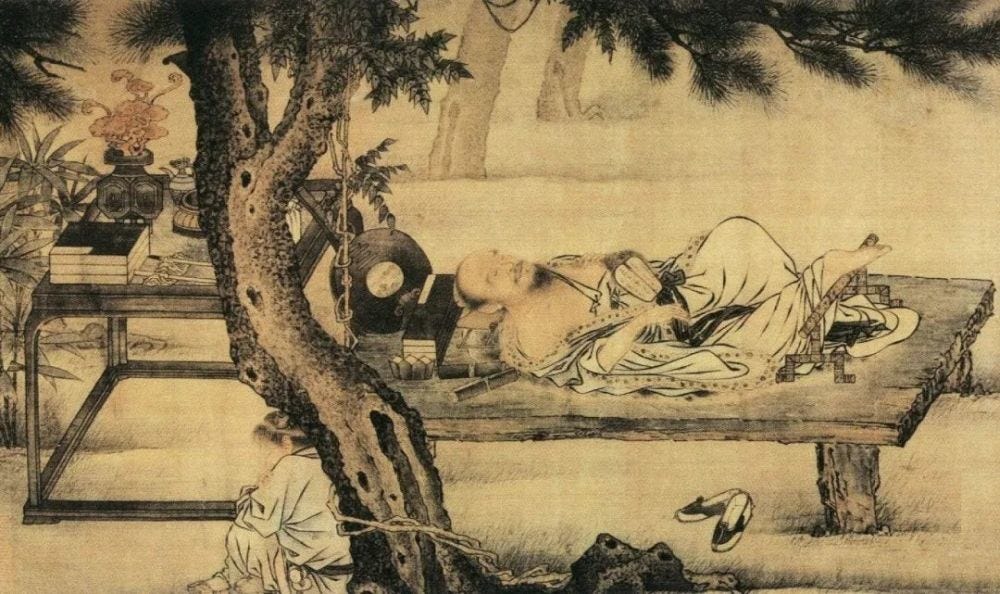

Zhuangzi

Taoism has an interesting relationship to the use of tools. On the one hand, it seems to say the perfect usage of our bodies in any craft relies minimally on any extrinsic helpers. On the other hand, like in the story from Zhuangzi quoted above, it is recognized that certain activities (like cutting meat in a neat fashion) necessitate the use of tools; and certainly alignment to the Tao relies on how naturally and expertly the tools are used, not in avoiding their use entirely.

In a sense, our mental faculties are like tools. We use our minds for instrumental purposes; namely for communication, organization of cooperation and discovering new ways to interpret the world that help us better adapt to it. Thus, one can use one's mind skillfully or poorly; and, like the butcher's knife, how skillfully one employs it determines the toll it takes from its application. Fittingly, the PIE root *skey- behind the English words science and consciousness means to dissect, as with a knife!

My favorite form of meditation is an intentive disengagement from thoughts that appear in my stream of consciousness. That is, I make it the point to refrain from indulging in an active process of thinking: I allow the thoughts to happen, and instead of reactively or proactively engaging with them, I return to an awareness of my immediate surroundings, or my breath.

One day upon practicing this kind of meditation on a walk, it dawned on me that it is analogous to how Zhuangzi's master butcher employed his knife. He found the spaces between the joints, which he followed with his knife in order to minimize the resistance the blade would have to endure. But he could only find those spaces by listening to the structure of the flesh; not by forcefully hacking at it. Hacking at it would have accomplished his primary goal of cutting flesh, to be sure, but it would have worn his blade out eventually and the result would not have been as pretty.

When you think like the dexterous butcher used his knife, you do not use force: you refrain from engaging with thoughts impulsively, and instead let yourself pick up the thoughts that are worth engaging with, if any such happen to arise, through the path of least resistance. In the spirit of wu wei, you navigate in the space between the thoughts, in the awareness wherein your thinking happens. And like the dexterous butcher's knife, your mind never becomes dull but remains ever sharp.